There is nothing easy about the plane from New York to my connection in Oslo. I don’t mind long plane rides, actually find the limbo of transportation liberating. When else can you read a novel cover-to-cover or spend five uninterrupted hours learning phrases in the language of your destination? But this time, I feel the improvements in my pained back over the last two weeks being reversed by the uncompromising lumbar positions of plane compression.

I feel the fading calluses on my fingertips and am inexorably aware that my guitar is not in the overhead bin. Leaving it was a wise decision, I remind myself, since playing it was making my back problems worse. But it’s the first time I’ve left it in 16 years, and my inner monologue wonders if I’ll ever be able to play it like I used to. How much of our lives are spent worrying about problems that can’t be solved at that moment instead of taking stock of how in that same present so many anxious problems of the past have long been solved? Remember, you’re finally Asia bound, I remind myself a million times.

In Olso I check my email and find that two Filipinos have responded to my couch surfing request and say they would be happy to host me. I haven’t couch-surfed since 2010, but am feeling I’d rather start this trip with people who know the city than going it alone. Plus it’s kind on a budget made complicated by the shooting pains down my left arm, which has slowed the trickle of income from writing.

Awkward naps on the flight to Bangkok cause both arms to go numb. It’s freezing onboard, colder than any flight in memory and I wonder if the thermostat was set in the same board room meeting where the movers and shakers at Norwegian Air decided to charge for blanket use.

I glance at the monitor in the seat in front of me. I’m just north of Bagdad, six hours from Bangkok, further east than I’ve ever been. I focus my thoughts on the fact that this is really happening. Whether or not it was a mistake to go ahead with the trip is immaterial, because I can’t go back now.

The strange characters on the signage in Bangkok’s airport are definitive proof that this is a distant elsewhere to anywhere I’ve ever been. Allain de Bolton writes in The Art of Travel, “It is not necessarily at home that we encounter our true selves.” I feel most alive when navigating through novelty. Armed with just an address of my Filipino hosts in a city of 8 million, I board Bangkok’s sky train and find my way to the subway looking for the Huai Khwang District.

On the 25 hours of plane and airport time on the way, I’ve learned the phrases I need to point to an address and ask how to arrive. Everyone I interrupt with “Kor Tor Kap—excuse me please,” is helpful and smiling. It is so different than riding New York City’s subway because I am in no rush to get anywhere. I have unaccounted months before me to fill with the geographies, company, and activities of my choosing. If I don’t find where I am going, I will still arrive somewhere, anywhere.

I arrive at the right station and slowly wheel my luggage through previously unfathomed streets, careful not to strain my back. Sawadi-kap, I smile at Thais in the street and point to the address. They point and nod and I ping-pong in various directions until I find the right apartment building.

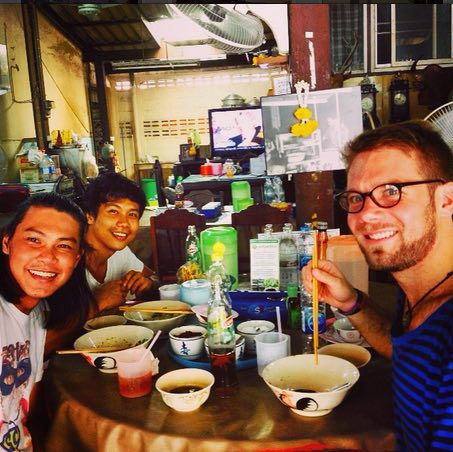

My hosts—Drexel and Melvin—are smiling Filipinos in love with their expat lives in the bustling city of Bangkok. We grab lunch and share the stories of who we are. These two amigos met at their gym in the Philippines and came to Bangkok together. As they explain, there is a brain drain in their country since the youth leave to find better opportunities and higher paying jobs outside. Melvin has two brothers, Drexel, like me, has nine siblings, but he only grew up with eight. When a set of twins was born, one of the boys was given to an aunt and uncle because they did not have any boys of their own.

Melvin describes dinner at Drexel’s house, “It’s crazy,” he says. I love to just watch. Everyone talks and talks and talks.” He echoes exactly what my friends say about dinner at the Armstrongs.

As we eat utterly delicious fried chicken and noodles, they unveil our evening plans—urban exploring of the abandoned 49-story Sathorn Unique Building in downtown Bangkok. The 80% constructed building was left to the elements during SE Asia’s 1997 economic bust.

In 2012, the first Thai urban explorers entered the building by sneaking past the guard of the Sathorn Unique Building. Nowadays, there is a set “bribe” to enter–100 baht for Thais, 200 baht for foreigners and if you are a superhero and can fly, it is free.

Part of these proceeds go to pay off the authorities who allow this dangerous tour of downtown Bangkok to continue. One death has happened. The police called it a suicide, the photographers’ friends claimed it was a murder, and I suspect it was an unfortunate accident, since an unaware eye lost in a camera viewfinder can be lethal in building featuring open elevator shafts and unforgiving ledges.

By the time we climb the 10th floor, the heat yields to rain that grows in intensity as we climb higher. Lighting cracks, striking other buildings and keeping us one floor beneath the roof. I had never been inside a thunderstorm before and it’s as exhilarating as it sounds.

We are level with lighting and thunder storms through shuttering concrete. As if it’s cosmically planned, the storm dissipated just as the sunset painted the clouds and city lights begin fulgurating in the city below.

Bangkok sits majestically below. This evening is the start of Songkran, and the city is about to turn into a 3-day water fight that will leave me drenched from laughing Thais spraying me with Super Soakers.

I have arrived at the craziest time of the country, and the festivities of the next day will feel like an arrival celebration. Despite my still bickering body, I’m grateful for the past decision to go through with my plan and feel confident I’ll find healing here and then so much more not-yet-known things.