People do different things for different reasons, and in different ways. That’s why you can’t put homeschoolers into one defined category. From the misguided homeschooling parents who fed one their son only lettuce and watermelon because they thought he was the reincarnation of Christ—I am not making that up—to the ones who do it because they want to give their kids the best education possible, homeschoolers fit into as many categories as they defy.

I went to a “normal” grade school. But after my mom wrote an article on homeschool a series of contemplative dominoes were put into motion and my parents decided to yank us out of school and homeschool us until high school.

Even if my siblings and I hadn’t been homeschooled, we would likely still be borderline on most normalcy tests. When I did return to a formal school setting in high school, I had a new nickname every week: The-kid-who-put-the-live-lobster-in-the-toilet, the-kid-who-hoisted-a-fish-on-the-flag-pole, the-kid-who-put-alarm-clocks-in-the-ceiling-tiles-that-went-off-moments-before-a-test, etc.

Indeed, creativity has always ally and enemy. In a formal school setting, it netted me plenty of tickets to the principle’s office.

Though I do not know all the reasons why some parent’s home school some kids, or even why my parent’s ultimately decided to take me out of school in the fourth grade, I do know what it did for me: almost got me arrested for transporting allegedly endangered butterflies across international borders.

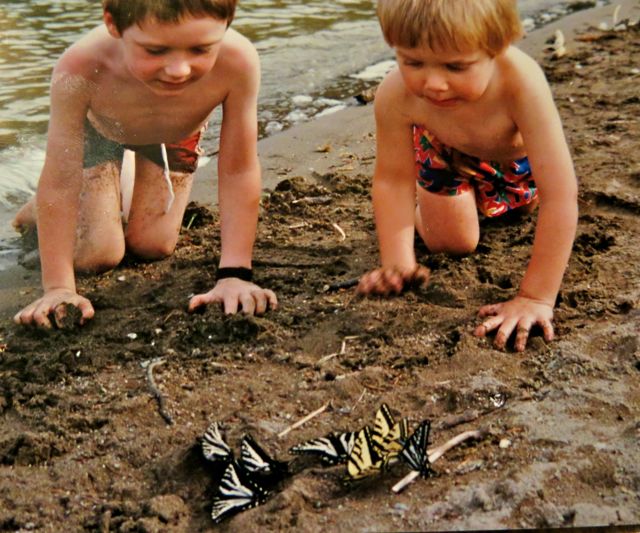

When a band-o-homeschool families got together for a lakeside beach trip one May day, I brought my portable microscope to look at microbes in the pond-muck. I knew a certain seventh grade girl that I had a crush on was going to be there, and assumed my microscope would be a conversation starter and she would leave her beach towel on the sand to investigate what I was looking at under my microscope. She stayed on the beach. In reality she was about as interested in looking at insects under a microscope as she was strep throat.

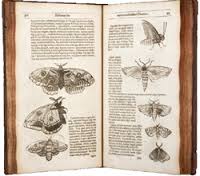

Homeschooling had obviously warped my mind and in a homeschool setting I was permitted to further warp it being my wildest warping dreams. In a conventional academic setting, insects occupy a single chapter of most science classes. For me, they filled an entire chapter of my life. I would rush through my other subjects and promptly be out the door with my butterfly net and jar. There was a microscopic world out there, and I needed to capture it and know its name. My room at the time was littered with stacks of college level books on insects.

While other kids were borrowing the Hardy Boys and ,I was walking out the door with titles like, “A Theoretical Framework for Understanding the Seasonal Behavior Patterns of Lepticorus Trivitatus. When I read that some cultures eat insects, I began frying grasshoppers in the kitchen.

When I was thirteen, a mission group from my church was going to be traveling to Guatemala to build houses for the needy. After my parents gave me permission to go on the trip with the money I had been saving for years from a paper route, I faced a jungle of exotic Central American species of insects for the taking.

When I was thirteen, a mission group from my church was going to be traveling to Guatemala to build houses for the needy. After my parents gave me permission to go on the trip with the money I had been saving for years from a paper route, I faced a jungle of exotic Central American species of insects for the taking.

Confined to “boring” species of the temperate Midwest, the colorful doors of the tropics were about to burst open. With a suitcase full of insect collecting equipment and a Spanish phrase book, I boarded a plane. I was the only thirteen-year-old on an otherwise all-adult mission group. They soon learned what sort-of weirdo they had on their hands when on the first night I did a victory dance on Antigua, Guatemala’s cobblestone streets upon capturing the cockroach they ran squeamishly away from.

Cannot to finish this house and catch some cockroaches

While everyone else in the mission group was absorbing the new world they found in Guatemala, I was absorbing two—the macro one that consisted of a foreign culture and language, and the micro one beneath everyone’s feet. People started catching on. Children at the charity our mission was affiliated with watched whom they had dubbed el Hombre Insecto pinching bugs from the foliage. They joined in the fun and started looking for insects with me. We could not speak the same language, but we could still share the victory of a discovered beetle. My Guatemalan collection, thanks the help of the school, grew and my pride swelled.

On the plane home, my bag was filled with Ziplocs of soon-to-be-categorized insects. I was also carrying bugs I had not tried to collect. I was feverish and a babbling stomach caused me to frequently run anxious to the restroom (A lab test back home would later confirm that I was carrying a worm colony).

15 year on, my parents attic is still home to some of those insects

I felt like death and was in no mood to argue when a customs official asked to search my bag. Begrudgingly, I put it on the aluminum counter. His gloved hands then began pulling out a gambit of suspicious materials.

Professional entomologists often carry chemicals for killing insects, syringes for safely injecting these chemicals into jars, and of course, they carry insects. This would be permissible for a researcher with the proper credentials. But finding these things in the bag of a thirteen-year-old boy was not something he saw everyday.

As I held my a angry stomach, the agent waved his supervisor over. They turned over the contents of my bag to look at my strange items from different angles and puzzled over which laws I was breaking.

“What are these for?” They asked me.

“They’re for insects.” I said, disgusted with American customs ineptitude towards the exciting field of entomology.

“For insects?” the agent repeated interrogatively.

“Yes,” I retorted, indicating a black plastic bag that held my treasures.

The agent opened the bag to find my dozens of Ziplocs filled with dead insects. He looked about to lose his lunch, but when he got to the butterflies, he got serious.

“You know it’s illegal to take endangered species, dead or alive, out of a country?” he asked in an official tone.

“Yes,” I said, beginning to worry that I could lose what were at that time my most valuable possessions. “But none of these are endangered!”

“How do you know that?” He asked me.

I looked at him like he was the child. You know nothing John Snow, said my very being. “You can look them up if you want, but none of these are endangered. I would know if they were.”

The agent looked like they had not covered this situation in his training. In the end, despite the fact that he said my bag was one of the “most suspicious bags he had ever seen without making an arrest”, he let me and my insects fly home and soon each insect was proudly pinned and tagged.

The things we are certain of in childhood often don’t always adulthood. While I still possess an obscure store of now never used knowledge about insects, insects exited my life about the same time girls started talking to me. I still find them fascinating, as I find most things in this wondrous world we are part of intriguing, but it was not something I ended up making a career out of.

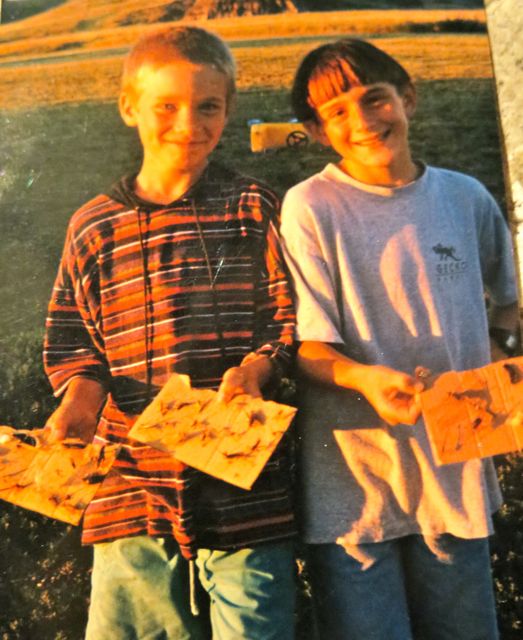

Apparently the interest in insects was there pretty early on . . .

Homeschooling for four formative years allowed me to spend hours a day studying insects. But something more valuable was happening: I was learning how to learn, learning how to teach myself the things I wanted to know, without needing any teacher other than myself to acquire the knowledge I thirsted for.

I learned that there are no bits of knowledge off-limits to anyone. All you need is the desire and the commitment. With these two things the vast, sometimes daunting world shrinks to a more manageable size.

This maybe, is the most valuable lesson of homeschooling. Learning wasn’t about grades. It was not a competition to do better than my peers on tests. I had not peers but beetles and butterflies and there was no lesson plan standing in the way of my running full speed towards the knowledge I wanted to know.