Real life happens out in the world. Time away from it reconnects us with the world and disconnects us from the dopamine-fueled compulsions the Internet can cultivate.

As I’ve written about in a previous post, if I had not met Opp, it seems unlikely I would have made it to the monastery in Thailand. When he left me at the monastery, he told me to call him when I was ready to leave and he would pick me up. “Okay,” I had said, “I’ll call you in seven days.”

As I’ve written about in a previous post, if I had not met Opp, it seems unlikely I would have made it to the monastery in Thailand. When he left me at the monastery, he told me to call him when I was ready to leave and he would pick me up. “Okay,” I had said, “I’ll call you in seven days.”

“Or,” Opp said, “call me in five days, call me in three days, maybe you’ll find you do not want to stay seven days.”

So seven days later, I call from the monastery office. He seems thrilled to hear from me. “Okay,” he says when I tell him I’m ready to leave, “I will be there to pick you up one hour.”

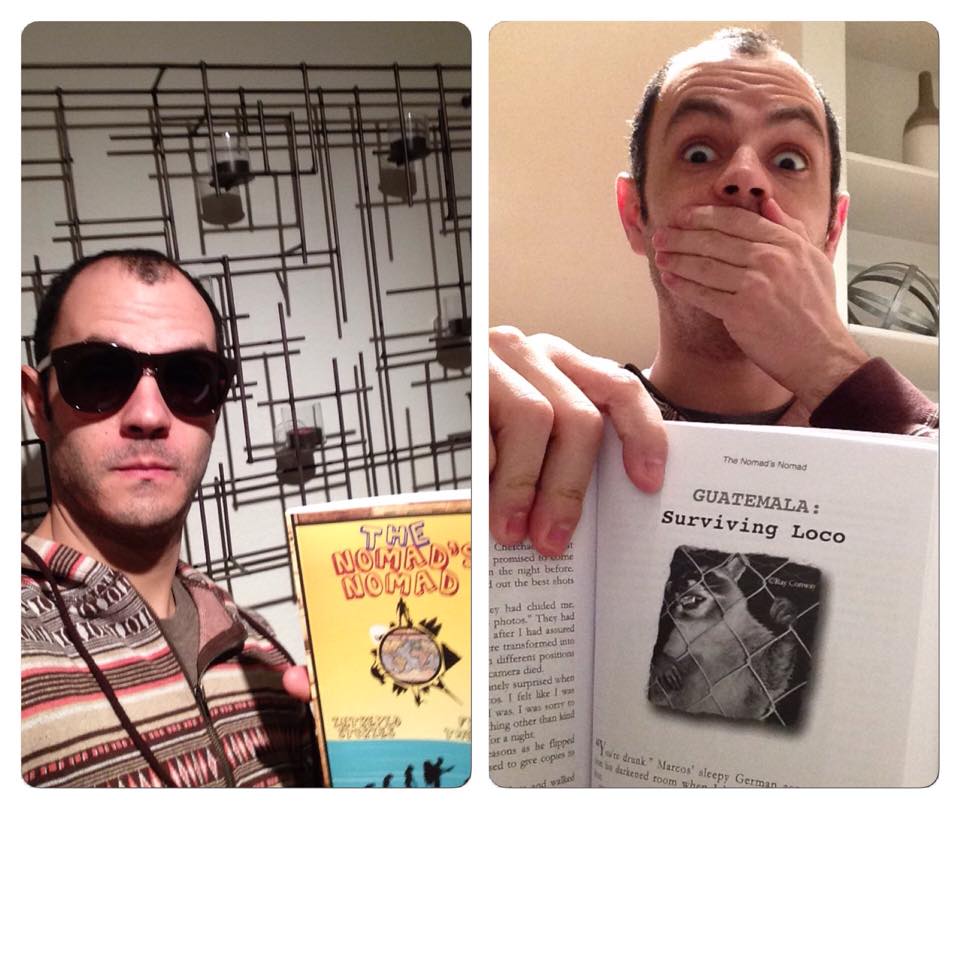

Opp seems impressed me as I buckle in his car. “Did not think you would make it one week,” he says. “And this morning, before you call, I think, it has been seven days, Luke will likely be calling today. Then, you call.”

He asks me where I am going next, and I say that I did not know yet, haven’t thought that far in advance. Perhaps on to another temple, perhaps not.

“If you could take me to a place that has the Internet, I’ll be able to figure that out,” I tell him

“Please,” he says, “come back to my car wash shop and here you may use the Internet at my house.”

So I was taken to Opp’s car wash/house. And after a week without the Internet, I reconnected myself to the digital world at large.

During time away from the net, you always think there will be so much that you missed. But really, it’s possible to disconnect yourself for a week, for a month, for a year, for some a lifetime, without missing much. Real life happens out in the world. Time away from it reconnects us with the world and disconnects us from the dopamine-fueled compulsions the Internet can cultivate.

The Sanctuary Thailand

Sanctuary Bound

In my inbox there is an email from Romi, an Australian writer who works for The Sanctuary on the island of Phangan, off the coast of Thailand, ten hours by train south of Bangkok. The Sanctuary was recommended to me by my friend McKenzie who lives in Hong Kong when she learned of my back injury. I’m still carry the complicated pain of it with me, and The Sanctuary bills itself as a yoga retreat center and haven of healers. So seems like just the place to get my back problem figured out. I’m not due anywhere for five weeks, when I’m supposed to meet my brother in Cebu, Philippines, so I have plenty of time to be anywhere.

I decide to stop off Bangkok, retrieve my computer from my friend Drexel’s, see a legit doc at the Bangkok Hospital, and then head to the Sanctuary. If a week or so at a healing haven on a beach doesn’t show me some improvement, then all travel bets are off anyways.

In With The Locals in Offbeat Thailand

Opp’s home is humble and homely. It is connected to the car wash business that he owns. Outside it is hot, near 90°. His two employees lounge about, no one is coming today to wash their car.

Opp brings me a bottle of water. “Please,” he says, “be welcome to stay the night to join me and my wife for dinner.”

I tell him that sounds nice. Opp’s mother and two kids are in Bangkok for the evening and in his backyard he leaves his mother’s small house at my disposal.

The Gifts The Visitor and The Visited Bring Each Other

In his backyard, we are joined by one of Opp’s friends, a local politician. Opp and he drink whiskey and teach me how to play Thai chess. In one spark of thought, I am transported to dozens of places across several continents. I think of the family in Peru, whom I befriended 2007 and stayed with for a week Lima instead of going to Machu Picchu. I think about the family fishermen I lived with off the Caribbean coast of Colombia. . .

This is what comes to mind when I think about travel. Travel is many things, but at it’s most beautiful it is this, befriending families, connecting with unlikely strangers, being welcomed simply because you are foreign–parties on both sides of the equations feeling fortunate to have met–one side making friends across the world, the other side making friends from across the world.

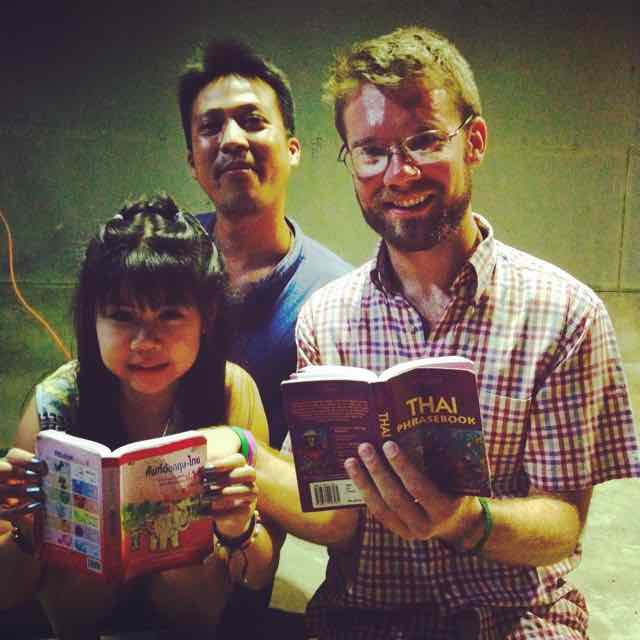

“Well,” I say, “I would like to learn Thai, so maybe we will make a good team.”

So I stay another night. I meet Opp’s mother, his shy son who is absent from dinner so that he can play video games and watch cartoons on his iPad, and his daughter, who is thrilled to share with me what English words she already knows and keen to learn whatever new words I can provide her.

During dinner, she runs to give me various presents, a cookie, some candy, her Thai/English dictionary. I distribute Guatemalan friendship bracelets to Opp’s family and teach them to howl at the moon.

After dinner, we are joined by several of Opp’s friends, all local politicians, for a game of Thai chess.

The next morning after breakfast Opp and takes me in the sidecar of his motorbike to the bus station so I can catch a ride back to Bangkok. His daughter rides along to see me off.

I leave hopeful and hopeless. The mind is an interesting container, capable of holding many contradictions. I’ve just had an incredible week, living in a monastery and connecting with Opp’s family. But on the jostling bus ride, my back and neck ache, and I wonder if maybe it’s even worse than before I set out for the monastery. It’s a war in my head, good thoughts trying to push out anxious ones. You’ll figure this out, I tell myself. And so it’s a day back in Bangkok, to see a new doctor, and then to the beach–if I can’t be 100%, then why not have a wounded wing in paradise?