I not sure how to tell you this story. If I introspect, I’m uncertain of either side of an extreme—worried that the medium of writing won’t throw the curtain separating a happening and it’s recounting far enough for you to peer behind, and also fearful it will swing too far, leaving me exposed.

I’ll do my best and follow Hemmingway’s advice, “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know.”

Samuel and Simon’s Story

Their parent’s graves are marked only in their memories. With his younger brother beside him, Samuel pointed to a vegetable garden where beans had just sprouted, “My father is buried there.” A few yards away, he pointed to a patch of Nepi grass, the kind they feed to cows, “my mother is buried there.”

He signaled the graves without emotion, like he was pointing out the plants growing above and not the final resting place of both his parents. His father died

in 2005. His mother in 2010. Both victims of AIDS.

“The fathers, usually die first,” Calvin said. “They are more likely to deny they have the disease and refuse treatment.”

Tyler, Calvin and I followed the two boys on a narrow, muddy trail to their grandparent’s house. The elderly pair have looked after them since their parent’s death, their children’s death, and do the best the can. In the scheme of things, this is very little. Not enough to keep them in school or provide them with more than one meal a day.

Their grandfather is a graying man who supports himself with a cane. At our worksite, though he was too frail to help with the building, he used a machete to fashion Tyler and I shovels from tree branches.

Their grandmother is a trembling woman with a strained gait.

Both exude an inner strength that seems to stem from a stubborn defiance. That’s one way of interpreting their demeanor. It might be just as accurate to write that both carry an inner grief, the sort that hardens like a shell around you.

But really, I’m writing fiction when I type things like this. I don’t personally know them, their life, or their plight and all I’m doing by writing as if I am privy to their inner states is witling reality into a shape that fits my worldview, carving the impenetrable into convenient, chewable bites.

Samuel and Simon’s Promise

We met Simon and Samuel after day one of constructing a house we are building for them. Calvin and Joash, my Kenyan brothers, grew up a half-kilometer from them. By the time their father died, Calvin was a junior at Saint Mary’s Central High School in Bismarck, North Dakota, thousands of miles and a world away from the hills of rural Kenya.

We arrived at their grandparent’s home just as the sun was setting and were seated around a battered table in their mud hut. The cicadas began their song, one that would grow in volume as the darkness increased.

When night fell fully, we were left in darkness. There were no streetlights outside, no artificial illuminations—complete and utter darkness. There was not enough money left over after buying food for them purchase candles.

After a half an hour in darkness, the boys’ uncle left to borrow a paraffin candle from the neighbor. “You see,” Calvin said, “They don’t have a way to do their homework after dark.”

To start the meeting, Calvin turned to me, indicating that I begin. This was as solemn as an occasion as I’d ever been part of. On both sides of the table, promises whose obligation would extend for years were to be made.

With Calvin translating, I explained to the two boys that Calvin’s parents had also died of AIDs. “Joash and Calvin,” I said, “Are my brothers who grew up in this same village. Now, Joash is studying to be a nurse and Calvin a doctor.”

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” I asked them. Samuel, the oldest, said he wants to be a doctor. Simon wants to be a pilot. Life’s deck is stacked considerably against either profession. In their situation, it would be a stretch even if their parents were still alive. But the same could have said of Calvin and Joash’s plans a decade ago.

“My brothers and I,” I told them, “Are going to make a promise to you. We promise to pay to keep you in school, the best school here, if you promise to stay in school and get good grades.”

“You have to get the best grades,” Calvin added, “number one and number one.”

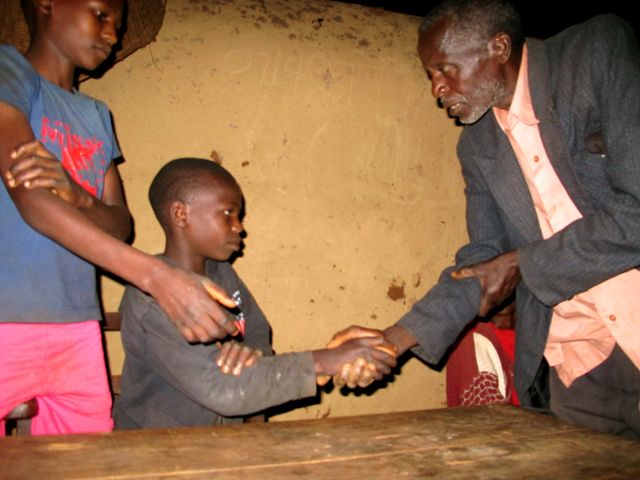

In the darkness, both boys nodded and promised this. They shook my hand. They shook Calvin’s hand. They shook Tyler’s hand. Their grandfather rose slowly from his chair and they shook his hand.

These were not the whimsical bargains of children, but the solemn promises of men who understood what their vow entailed.

Their uncle spoke and Calvin translated. He asked them to promise also to stop associating with bad influence who were wasting their time. They promised.

With the agreement on both sides made, the boys told us what they remembered about their parents. In African culture the dead and the living walk together. Those living carrying the spirit of those who have passed on with them in ways more tangible than we in West understand.

I’ve tried a few times to write what the boys said, but as I recorded our meeting, I think it will mean much more if I let them speak for themselves.

Before we left, the boy’s uncle told Calvin a story about his mother that she had never told him. After his father died sometimes when her sons were away with other relatives she would have to stay home alone. She was afraid of the dark, as many here are, worried of witches and other dangers that lurk in the night. Someone from Simon and Samuel’s family used to come and stay with her, so that she would not be afraid.

Calvin smiled, and laughed, “I never knew that.”

I’m not doing a great job of re-telling this story. I’ve called it a solemn occasion, and it was, but it was not a joyless one. There was laughter, jokes to be told, and stories told. It lasted well over an hour. Everyone who left did so fully committed to keep his end of the bargain.

Full disclosure: I have an ulterior motive in bringing you with us on this journey, to Africa and into these two-orphaned brother’s mud hut.

I hope that if you continue to read this blog one day soon, this year, I’ll have a tangible way for you to help kids in this situation. What has started out as abstract and one day “down the road”, has become tangible and now.

Working with my family, our friends and you if you’ll join us, I think we can do more than just help these kids. I think we can help hundreds, maybe thousands to have the opportunity to go as far as they push themselves. Life is anything but an even playing field, and that gives us the opportunity to give others the opportunities we have and they lack.

I’ve been given the gift meeting hundreds of people who are selflessly doing what they empower those around them. There’s still so much to be done. With just the amount Americans spend annually on makeup, we could stop world hunger and prevent death from curable diseases. Our governments do some, but they’ve left a wide gap. Only we can fill that.

On the walk back, my brother Tyler, who last year graduated from college and is still figuring out what to do with his life said, frankly, that helping people in situations like Simon and Samuel is what he wants to do with his life. He’s one of the most selfless people I know, and I don’t doubt he’ll make good on that goal.

We’re past the stage of thinking about what we can do; we’re figuring out how. But before we can do much legally, we have a few mounds of paperwork in front of us. I hope you check back when we are a few steps further down the road.

Or better yet, don’t wait for us. There are plenty of other foundations and charitable organizations–great ones–out there who could use your support, your time, your treasure or your talents.

Feel free to contact me if you’d like me to share some of my favorite orgs with you. And please share this story. We’re living in a world where the only walls separating “us” from “them” are the we build between us. A world where we needed be discouraged that the world isn’t perfect, or even fair. It’s never been. But we can pick our perch and reach for it.